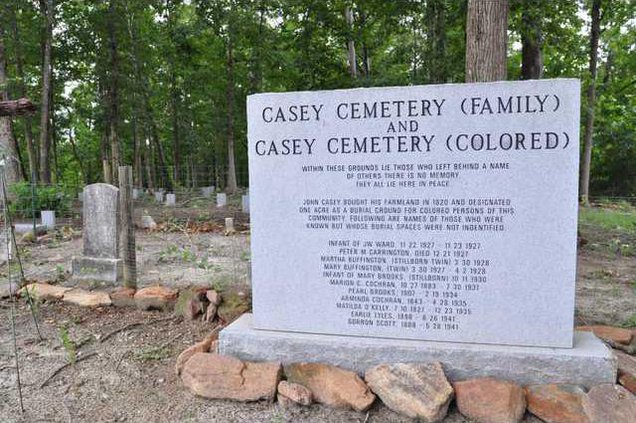

If you want to get an idea of how times have changed, take a trip to your local cemetery. Whereas families and community members used to join in the upkeep of their loved ones’ final resting places, that tradition sadly seems to have passed. "When we were growing up, we used to have Decoration Day on Memorial Day weekend. A bunch of people in the community would go clean it up," said Betty Petrie, a Dahlonega resident. "But then, Memorial Day got real commercialized. It became a holiday weekend where people would go someplace and the younger generations come along and that’s ‘play time,’ not ‘honoring your ancestors time.’" "Back then, you didn’t have the convalescent homes or societies that furnished help to the elderly," said Loy Saine, also a Dahlonega resident and Petrie’s cousin. "You maintained your own family at home. And when they passed a way, you made sure they were still taken care of. "You continued to honor them by taking care of their final resting places." Losing interest Like many other customs of yesteryear, the tradition of maintaining independent cemeteries isn’t what it used to be. Petrie, Saine and their cousin, Bobbie Butler, know that all too well. In the early 1800s, their great-great grandfather, Jacob Saine, deeded 2 acres of his property to the Methodist Church to build a sanctuary and a cemetery. Both were constructed, but 80 years ago, the old, log-cabin structure — Shady Grove United Methodist Church — was razed after the last of its members died. The Shady Grove Cemetery, which is located off of Camp Wahsega Road in Dahlonega, remained intact. Besides the Saines, there are three Confederate soldiers buried there. For a while, the Saine descendants and the nearby community maintained it. "All of our parents were sticklers about cemeteries," Butler said. "Mama would say, ‘You gotta get up there and put some flowers on the cemetery. You gotta get there and clean this up.’" Though time is standing still for the cemetery’s inhabitants, it continues to keep pressing forward for those above ground. As the years passed, the older Saine descendants died and their children left town. While the younger generations were focused on building their own lives outside of Dahlonega, they didn’t think very much about the cemetery’s upkeep. They just assumed the community would continue to care for it. After returning to their hometown, the cousins discovered that wasn’t the case. "It’s been neglected for a lot of years. Literally there are graves with trees growing up right beside them," Petrie said. "These big, woody ferns have taken over in many areas. You almost don’t see some of the graves because they’re just marked with rocks at the head and the foot." The cousins are now trying to pick up the torch left by their parents. They’re waiting for surveyors commissioned by the Methodist church to determine what the next step will be. "All we’re trying to do is get some interest in doing a really good cleanup and then maintaining the cemetery," Petrie said. "We’re willing and ready to do everything we can, but to my way of thinking, there should be some local ownership from the Methodist church (organization)." While the Saine descendants feel that having a church still on site would have prevented Shady Grove’s demise, others disagree. Twenty-three years ago, Charlie Teague discovered his great-grandfather was buried in the Harmony Hall Baptist Church Cemetery off Harmony Church Road in southern Hall County. Although the church is performing the basic maintenance like cutting the grass and trimming tree limbs, Teague says there is more work to be done. He says graves still need to be marked and existing tombstones need a little TLC. "There is great disrepair," said Teague, who moved to Gainesville three years ago. "I don’t fault the church because they’re doing the best they can, but it looks terrible." Some of the marked graves date back to the 1700s, he says. "I would like to see a special-interest group help clean things up," said Teague, 85. "I think we owe it to our ancestors to keep up their graves." Helen Thompson, a Gainesville resident, agrees. For the last several decades, she has been paying for a contractor to go out annually to clean up the Casey Cemetery off of Henderson Road in Gillsville. In the early 1800s, her great-great grandfather, John Casey, purchased multiple acres of farmland in that area, some of which he designated as a family cemetery. And though there was no formal deed, he also designated an acre of his land as a cemetery for the black members of the community. "Things were very different back then," Thompson said. "There weren’t as many laws, so it’s not unusual for there to not be a deed." As with the Dahlonega cemetery, the Casey cemetery also stood neglected as older generations died and children moved away. However, with the assistance of the Saving Graves organization, Thompson’s family was able to get it back on track. "They enlisted the help of volunteers and cleaned things up. There were vines out there as big as my wrist," Thompson said. "They also probed for unmarked graves." Although the 27 graves on the family side of the cemetery were marked, 159 of 197 graves on the black side were unmarked. To further beautify and add more dignity to the final resting places, Thompson’s family pooled their resources and purchased headstones for those unmarked graves. Recognizing that she’s getting older, Thompson has made arrangements for the cemetery, still owned by a Casey descendant, to be maintained after she’s gone. "We spent a large amount of money to get set things right," Thompson said. "There’s no way I’m going to let it go back to the way that it was."

Many old cemeteries fall into disrepair after descendants move on